BY TAMARA TABEL

There is a real cost to segregation — in lost income, lost potential, and lost lives.

Over generations, policies and practices have led to people of different races and incomes living separately from one another. What are the costs?

On March 11, Kendra Freeman of Metropolitan Planning Council in Chicago shared findings and recommendations from their groundbreaking Cost of Segregation report for the seventh session of A Year of Courageous Conversations presented by Urban Consulate at Barrington’s White House.

Inherently, we may recognize that separation takes a toll on individuals and our society. But MPC’s two-year study of Chicago — ranked as one of the most segregated regions in the nation — put real numbers to this, determining the actual costs of segregation in lost income, lost potential and lost lives. The data demonstrates that by reducing segregation, we can dramatically improve economic outcomes — not just for the most marginalized, but for all.

Since 1934, Metropolitan Planning Council has been dedicated to shaping a more equitable, sustainable and prosperous greater Chicago region. As an independent, nonprofit and nonpartisan organization, MPC serves both communities and residents.

As Director of Community Development & Engagement, Freeman oversees housing policy and equitable transit-oriented development programs and guides the organization’s approach to community engagement in research, policy advocacy and technical assistance. She holds a Master's Degree in Public Administration from DePaul University, is a licensed real estate broker, and serves as co-chair of Elevated Chicago and advisor to the Truth, Racial Healing & Reconciliation initiative of Greater Chicago.

History of Suburbanization

To briefly cover the “forgotten history,” as Richard Rothstein calls it, of how 20th century housing policy and real estate practices codified separation in the American landscape, Freeman showed this short video featuring MacArthur Prize-winning investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones from The New York Times:

The video explains how segregation in the suburbs began in the 1930s, when as part of the New Deal, the federal government implemented loan programs to help Americans finance home purchases. However, discriminatory “redlining” meant virtually no minorities could qualify for these loans.

The term redlining came from the government-generated maps where families living in green (“good”) neighborhoods could receive loans, while families in red (“bad”) neighborhoods could not.

And who lived in these “hazardous” red areas? Black Americans and other minorities.

This policy, along with discriminatory practices by suburban developers barring minorities, systematically prevented minorities from getting home loans.

From 1934 to 1968, only 2% of home loans were to non-white families.

These policies had devastating effects over time, disadvantaging families in “red” areas by limiting their ability to generate wealth, trapping them in poverty and in their current neighborhoods.

In comparison, families in “green” areas were able to compound their wealth. They could invest and buy even better homes, send their children to college and pass on their wealth and advantages to future generations.

This prosperity also attracted new businesses, further advancing property values and allowing for more tax funding for better schools. Segregated neighborhoods created segregated schools.

“The truth is, black children are more segregated in schools now than in any time since the 1970s,” said Hannah-Jones.

With tax dollars from higher property values and more business, white schools have better facilities, teachers, supplies.

“Minority schools are massively underfunded,” added Hannah-Jones. “They are less likely to have AP classes, science and math. And the least likely to have experienced and qualified teachers.”

Unfortunately, this discrimination is not a thing of the past.

“Regularly, black home buyers are still charged higher rates on homes than whites,” said Hannah-Jones. “Even when they have the same credit.”

“Black and Latino home seekers experience 4 million incidents of illegal housing discrimination each year.”

After watching the video, Freeman invited the audience to discuss what we learned, what surprised us, and what challenged us.

One example: “Think about who is on HGTV,” said Freeman. “They are all white.” This is because their parents and grandparents were able to buy houses in the '30s and ’50s whose values appreciated, so they could lend money to their children to buy their own homes.

“The challenge is to dismantle structural racism,” said Freeman. Yes, behaviors and attitudes — but also policies and practices.

How does Chicago compare?

Freeman shared a redlining map of Chicago from the 1940s.

Green areas were considered very desirable (like the North Shore)

Purple indicated areas that were still desirable

Yellow indicated declining areas

Red showed those areas considered “hazardous”

The yellow and red areas were primarily concentrated on the South and West sides.

The map is still valid today. Chicago remains one of the nation’s most segregated regions — 5th highest when looking at combined racial and economic segregation across the country.

Although we share company with other cities like Philadelphia, Newark and Cleveland, the region has done little to change its ranking.

The study is clear:

“It is not inevitable that a city and its surrounding suburbs are segregated to the degree that the Chicago region is.”

“Other regions across the country are similar to Chicago in terms of population and demographics, but are more racially integrated among African Americans, Latinos and whites.”

“Some regions have also dramatically reduced segregation from 1990 to 2010: Atlanta improved from 21st to 41st most segregated, while Chicago only moved from 8th to 10th.”

What is the cost?

What does it cost all of us in metropolitan Chicago to live so separately from each other by race and income? The study concluded that by reducing Chicagoland’s segregation to the national median, we could:

Raise the average income for Black residents by $2,982 per year

Raise the region’s income by $4.4 billion

Increase the Chicago region’s gross domestic product by ~$8 billion

Decrease homicides by 30% — saving 229 lives in 2016

Increase the opportunity for 83,000 more people to earn bachelor’s degrees

Gain some $90 billion in total lifetime earnings

In 2010, a 30% lower homicide rate would have resulted in 167 more people who would have earned over ~$170 million in their lifetimes; the region would have saved ~$65 million in policing and ~$218 million in corrections costs; and residential real estate values would have increased by at least $6 billion.

Moving Towards Equity

So, what do we do about it? What policies can we implement to build more inclusive communities in Chicagoland?

Freeman shared that it is important to acknowledge racism and segregation — and who is benefitting. Then use framing of equity and inclusion, focusing on equitable practices that lead to equitable outcomes.

“We need to focus on those who are worst off — closing the gaps so that race does not predict one’s success, while also improving outcomes for all,” Freeman said.

To achieve this, we must move beyond “services” and focus on changing policies, institutions and structures.

To illustrate, Freeman shared the classic equity example — sidewalk ramps. The ADA requiring sidewalks to be changed to make them more friendly for people with disabilities, especially those with wheelchairs and walkers, benefitted all of us, allowing easier access when we have strollers and bikes, too.

“Equity is the systematic fair treatment of all people that results in equitable opportunities and outcomes for everyone.”

Recommendations

Given segregation’s negative impact on equity, what can we do to change the patterns of racial and economic segregation so that everyone living in our region can participate in a stronger future?

Dismantle the institutional barriers that create disparities and inequities by race and income

This is known as racial equity framework, and it is a practice that everyone can adopt: government, private sector, philanthropy, community organizations and individuals

Pursue policies and programs that can be implemented right now:

Target economic development and inclusive growth

Create jobs and building wealth

Build inclusive housing and neighborhoods

Create equity in education

Reform the criminal justice system

Some progress is being made. For example, Cook County has centered racial equity as a main priority. Evanston has implemented a reparations program to return money to the community to assist in home buying and other uses.

Dismantling Barriers

We each need to do our part to acknowledge racism and drive change.

Dr. Reverend Zina Jacque challenged us to cross barriers and immerse ourselves in worlds beyond our own to learn about each other.

“Immersion. Be willing to immerse yourself. Take a risk and be better. Answer the call to go further.”

“What is the cost when we find it too frightening? What keeps us unwilling to try?”

* * *

Challenging Separation is the seventh monthly session for A Year of Courageous Conversations exploring how to foster greater inclusion & belonging in our community. Presented by Urban Consulate at Barrington’s White House in partnership with community advisors, the series is made possible thanks to support from Jessica & Dominic Green, Kim Duchossois, Sue & Rich Padula, Barrington Area Community Foundation and BMO Wealth Management.

REPORTING BY TAMARA TABEL

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LINDA M. BARRETT

VIDEO BY DELACK MEDIA GROUP

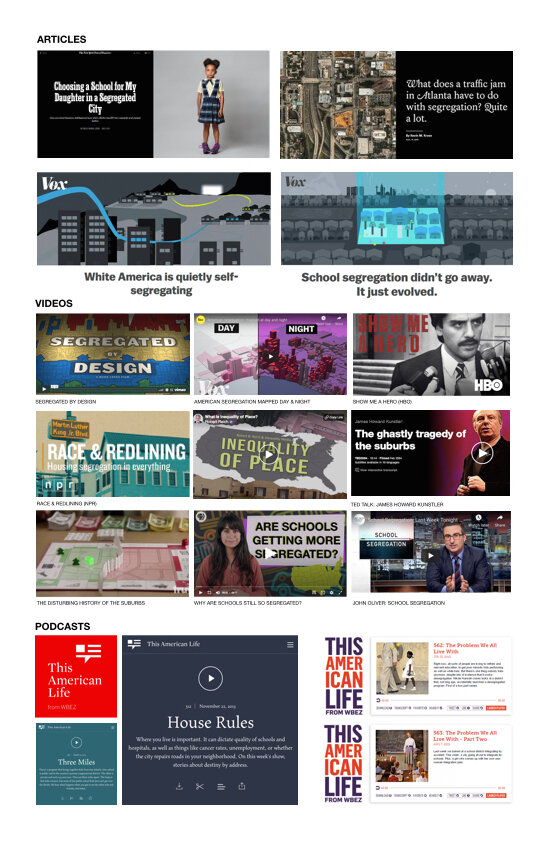

RESOURCES

SYLLABUS

RECOMMENDED PROJECTS

Tonika Lewis Johnson's Folded Map Project visually connects residents who live at corresponding addresses on the North and South Sides of Chicago. She investigates what urban segregation looks like and how it impacts residents.

To fully understand the deep roots of segregation in America, we must go all the way back to the origins of our nation. The 400 Years of Inequality project from Dr. Mindy Fullilove and partners offers guides for discussion and a detailed timeline here.